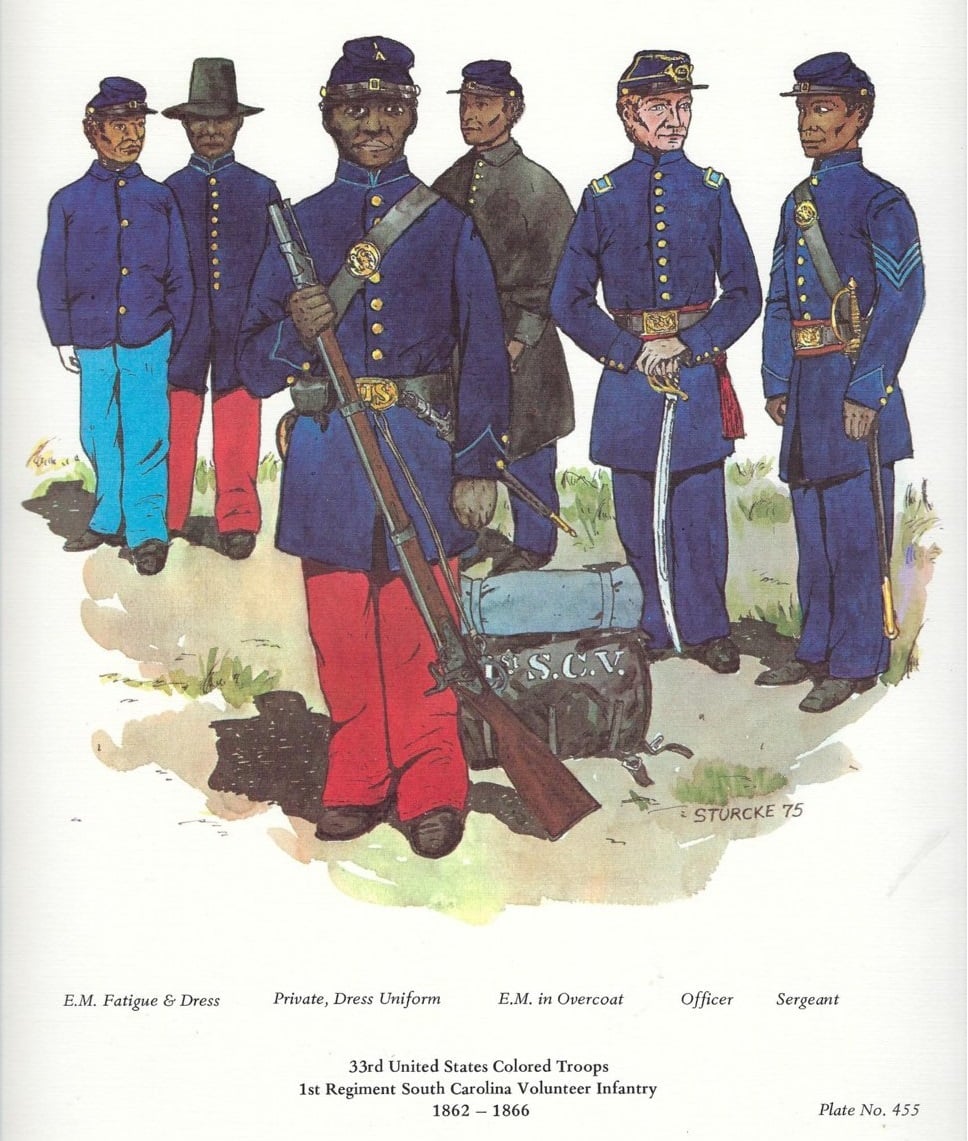

The first Black Men officially recognized as Soldiers of the United States were slaves. The unit was known as the 1st Regiment of South Carolina volunteers; it was created as an experiment in November 1862. The theory at that time was that the War Between the States would last quite a while; therefore using black soldiers to fight for the Union would save the lives of many white men. The experiment worked and almost 180,000 black men participated in the war. Approximately 33,380 lost their lives in uniform.

Fortunately the spirit of the black Soldier was such that they were never a disgrace to our people or our country. They distinguished themselves as fearless warriors capable of most any mission. Congress had honored many Black soldiers for their gallantry during the war, so it was no surprise in July of 1866 when it voted to permanently add 6 exclusively Black Regiments to the United States Army. A new chapter had been added to American military history. The new Regiments included the 9th and 10th Cavalry and the 24th and 25th Infantry. All of the units were destined to create a glorious place for Black Men in our history, but this article will concentrate on the Cavalry Regiments.

The Ninth Cavalry came into being at Greenville, Louisiana; the Tenth was organized in Ft Leavenworth, Kansas. Both units shared the same misfortune early on. Discrimination in the society at the time kept each unit from ever receiving its fair share of supplies or accommodations. Almost unbelievably though, the Army brilliantly staffed these units with remarkably competent Commanding officers. The officers were exclusively white but, those that chose to serve with these units were quick to realize they could not have served with better soldiers anywhere.

Civil war veterans both, Colonels Edward Hatch (9th Cay.) and Benjamin Grierson (10th Cay.) were to fight many a skirmish against discrimination on behalf of their Black Troopers. The Ninth Cavalry was especially lucky even before it was formed. The original selection to command the unit was another Civil war veteran who was well thought of as a distinguished officer. This supposed great officer was George Custer; he went on to become the commander of the ill fated Seventh Cavalry despite his refusal to lead Black troopers. At the time many were surprised assignments to serve in Black units, because all other white officers that refused were only allowed to serve at lower ranks in the next white unit they joined.

The Buffalo Soldiers “A Living Legacy”

Custer though was destined for a more fitting punishment, that he received at the hands of other warriors he thought to be inferior.

As the units were being created, Army recruiters had a field day. They had little regard for the units they were helping to staff. The recruiters tried to sign up as many men as they could with little regard for the quality of the men they found. Despite the recruiting problems and the shortage of officers, the 9th and 10th Cavalry moved in 1867 to the Great Plains of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona.

The 9th and 10th were assigned with pacifying, exploring and finally surveying the regions they patrolled. This put them between many treacherous adversaries and sometimes openly hostile settlers. The Indian tribes of the region that clashed with the Troopers were:

Apaches Comanche’s Arapahos Kiowa Cheyenne.

There were Mexican bandits, cattle thieves, and just plain murderers that bore no resemblance to the gunfighters we see celebrated in movies depicting the west.

Probably the worst opponent the Troopers encountered in their ten years of patrolling the plains were the crooked politicians, and bigoted homesteaders/settlers. These were often supported by friends who had connections with the department of Indian affairs or the Army or some other organization that was more concerned with money than justice. Despite the open prejudice they had to endure they served with distinction and were awarded seventeen Medals of Honor as Enlisted men and their Officers received another six.

Somehow the contributions of the 9th and 10th Cavalry to settling the American west have been obscured. Only the Army journals have chronicled the exploits of our ancestors. These Army records have been the source of data for many history buffs who have written many books on the subject in the past 60 years. As of yet these works remain known only to scholars and those with a desire to know the truth about the west.

The Buffalo Soldiers live on today, in several ways. One is the way we pay tribute to them by taking the name for motorcycle clubs. Another is demonstrated by the former members of the Regiments themselves. The US Army was forced to integrate by law in the 1950s.That meant the end of the traditional Black units. They saw service though in the Korean conflict and many of the members of the regiments got together and created an organization to carry on the traditions of their former units. The 9th & 10th (Horse) Cavalry Association is still in existence today.

In 1993 a memorial park was dedicated to honor the memory and contributions of the Buffalo Soldiers. The memorial is at Ft Leavenworth, Kansas home of the original 10th Cavalry. The memorial was dedicated by General Colin Powell and on hand of course was many of the Buffalo Soldiers who had served in the Korean War, or World War II, and there was also James Morgan who had run away from home at a young age and joined the Army. He was with the Buffalo Soldiers (24th Infantry) when they took San Juan Hill, before Teddy Roosevelt’s ”Rough Riders” arrived.

If you visit Ft Leavenworth, try and see the Buffalo Soldier memorial. Even if you never get to visit Kansas, stop by your local library, they have some great stories about these American heroes. Just look under Cavalry or US Army.